Composite rear leaf spring promises more adaptability and less weight.

Mention the term “leaf spring” and there’s a tendency to think of old-school muscle cars with unsophisticated, cart-sprung, solid-axle rear ends or, in motorcycle terms, prewar bikes with leaf spring front suspension. However, we are now looking at reviving the idea for motocross bikes.

In reality, while crude, old suspension systems often used leaf springs, the spring itself isn’t usually the source of their lack of sophistication. Chevrolet’s Corvette used transverse leaf springs on independent suspension from the second generation in 1963 right until the launch of the eighth generation in 2020, adopting composite plastic single-leaf springs in the ’80s. Less famously, Volvo uses composite, transverse leaf springs in several of its latest models. Used correctly, leaf springs made of modern materials can be lighter than steel coils, and in some instances their long, flat shape is easier to package. Composite leaf springs, made of a single piece rather than the stacked leaves of traditional metal leaf springs, also avoid the friction of the multiple leaves rubbing together, which was one of the main drawbacks of older designs.

Leaf springs have appeared on motocross bikes in the modern era before. Yamaha’s 1992–93 factory ‘crosser, the YZM250 0WE4, used a single composite leaf at the rear, its front end clamped under the engine and the rear bolted to a linkage below the swingarm, so as the rear wheel rose, the leaf flexed to provide springing. The idea was to clear the area where the rear spring and damper would normally sit, allowing a straighter intake path for the engine. A compact, rotary damper was also fitted and the bike was a race winner in both 1992 and 1993 in the All-Japan Championship.

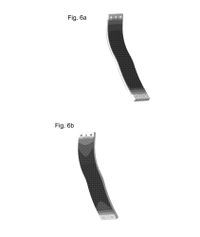

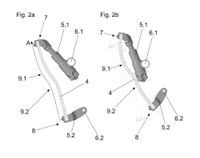

Our new design, revealed in a patent application from the Austrian company, refers to the Yamaha and points out similar advantages in terms of packaging, but adopts a different layout. As shown in the pictures, we put the leaf in a nearly vertical orientation, tight against the rear of the engine to clear the space normally filled by a coilover (the patent confirms that while its leading image shows the system overlaid on a picture of a conventional motocrosser, the coil spring shown in the image would not be present).

The top and bottom of the spring are each firmly clamped to the end of linkages. The upper linkage is pivotally mounted on the bike’s main frame, while the lower linkage pivots from a bracket under the swingarm. The result is that, as the swingarm moves upward, a bend is introduced to the composite leaf spring. To add adjustability, the upper linkage’s length is adjustable via a screw thread and an adjuster knob, making it easy to increase or reduce preload in the system. The patent doesn’t show a damper for the rear end but its text confirms that a conventional damper would be used to control the rear suspension. However, it would have to be more compact than a normal rear shock, or mounted differently, to allow KTM to take advantage of the benefits of the leaf spring, which are largely related to the space it frees up. The patent suggests this space could be used to make parts of the powertrain like the airbox, intake tract, or muffler, for instance, larger or more efficient. Additionally, the design could allow more flexibility of layout in future electric-powered motocross bikes.

The patent doesn’t show a damper for the rear end but its text confirms that a conventional damper would be used to control the rear suspension. However, it would have to be more compact than a normal rear shock, or mounted differently, to allow KTM to take advantage of the benefits of the leaf spring, which are largely related to the space it frees up. The patent suggests this space could be used to make parts of the powertrain like the airbox, intake tract, or muffler, for instance, larger or more efficient. Additionally, the design could allow more flexibility of layout in future electric-powered motocross bikes.

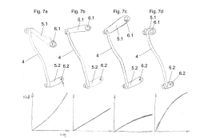

Beyond the packaging advantages, the system’s other benefit is its adjustability. Our patent shows how changing the length or shape of the linkages holding either end of the spring can alter the suspension’s behavior. In one illustration (Fig.7 in the patent), four different lever arrangements are shown to change the rear suspension’s behavior: changing from rising rate (7a) to constant rate (7b), and decreasing spring rates (7c and 7d). Those radically different behaviors are achieved without changing the spring itself.

As ever, a patent application is no guarantee that an idea will reach production, but the packaging advantages of the leaf spring rear end could become increasingly valuable, particularly in future as electric powertrains force engineers to rethink the conventional layouts that have been honed during a century of piston-engine bikes.

Post time: Jul-12-2023